On the Commitment Paradox

How Our Fear of Returning Reveals Our Fear of Staying.

It's 9:47 PM on a Tuesday, and I'm holding my phone like a divining rod, while my thumb hovers over the Netflix icon. The apartment is quiet except for the TV’s background noise and the distant sound of my neighbor's generator bleeding through the walls. I've been staring at this screen for three minutes now, paralyzed by the weight of choice.

My "Continue Watching" list mocks me with its abandoned series—Sandman at 73% completion, Seinfeld inexplicably stopped mid-season, Demon Slayer left hanging after a single episode. Below that, the algorithm offers its evening prescription; psychological thrillers, action comedies, foreign series featuring twisted characters. All of it new, all of it optimized for my demographic profile, all of it designed to capture my attention for exactly as long as it takes to keep me subscribed.

But there, buried in my saved list, sits The Big Bang Theory. I've seen it perhaps 10 times. I know most of the arguments between Sheldon and Leonard, every inconceivable moment, every time Rajesh tries to speak to Amy. There are no surprises left. And yet, something in me resists clicking on it. Why would I choose the familiar when I could discover something new?

This moment, this seemingly innocuous choice between the known and the unknown contains within it a theory(hypothesis, if that's going to make you feel better) that has been haunting me for months. What if our relationship with rewatching reveals something profound about our capacity for commitment? What if the person who can't bear to revisit Me Before You is the same person who bolts at the first sign of relationship turbulence?

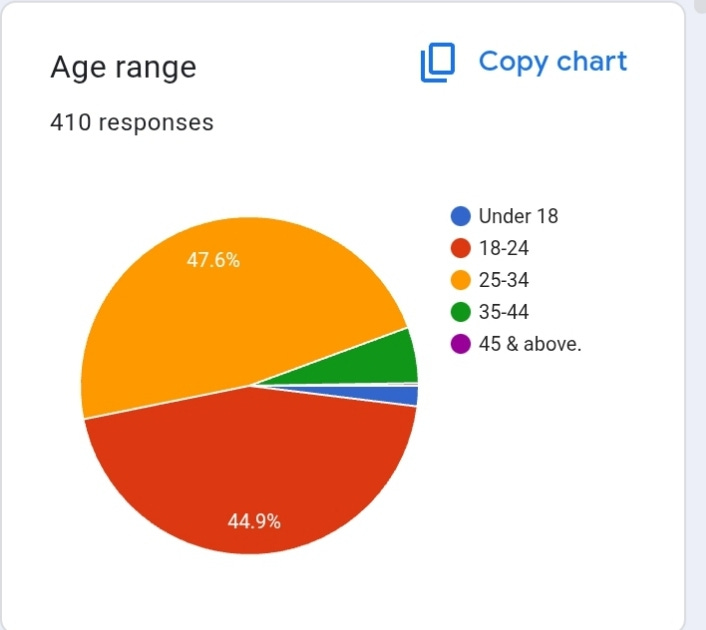

Last month, I tweeted my reservations on this topic and 410 generous individuals between the ages of 18-44 filled a survey anonymously about their media consumption habits and relationship patterns.

“The Queen's Gambit - a hitherto unremarkable orphaned girl, climbing the exclusive ropes of chess mastery, in a world where it was foreign for women to play chess let alone master it. Female excellence, the courage to achieve your dreams, and sheer goddamn display of brilliant chess, need I say more? As a woman, every scene where she defeated cocky men or simply showed the world her talent, meant so so much to me. I hardly get inspired, but this one certainly did spark a little something in me.”

What I hoped to find wasn't just data about entertainment preferences. I included a space where the respondents may reflect on their choices and how they feel about their favorite media. The results will eventually become a map of how we've learned to navigate love in the twenty-first century.

Roughly 32% of respondents said they rarely or never rewatch movies or series they’ve seen before. Of those, a majority cited either emotional discomfort, overstimulation, or a preference for novelty.

One respondent, an 18-24 year-old male, wrote, “I get bored easily. Once I know the ending, the magic dies.” And what if the individual who keeps revisiting a certain book or movie sees this as a standard for their own relationship dynamic? Just like this respondent who wrote: “The Tattooist of Auschwitz is the only book I’ve read multiple times, and for film, The Year Without a Santa Claus. These two media may seem completely different, but both have stayed with me in powerful ways. The Tattooist reminds me of the strength of the human spirit and the power of love even in the darkest places, while The Year Without a Santa Claus connects me to a sense of childhood wonder and the importance of hope and belief during tough times. Both represent comfort, resilience, and a reminder that light can exist even when everything feels heavy.”

I.

A respondent, more quietly, admitted, “Rewatching reminds me of who I was when I first watched it. And sometimes that’s too much.” She represents one of the 140 respondents—32% of the total—who actively avoid rewatching films or rereading books.

"I watched The Notebook obsessively after my first real heartbreak," she explained. "Now I can't even see the poster without feeling physically ill. It's like the movie contains all that pain in amber." You will agree with me that this isn't mere preference, and it's more or less, a protective strategy. This lady, like so many others, has developed what I've come to think of as an archaeology of avoidance—a careful mapping of cultural territories that have become too emotionally charged to revisit. It's like this situation where you lock a room where a loved one used to stay or you simply never revisit the house.

Consider what happens when we return to a beloved film or book. We don't just encounter the story again; we encounter ourselves. Past versions of ourselves, hopes we've abandoned, relationships that have ended, dreams that have curdled. The media becomes a time machine, and time machines, it turns out, are dangerous vehicles for those who've learned to live only in the present tense.

The survey further revealed that 110 respondents—more than a quarter—explicitly associated their favorite media with past lovers, grief, or phases of life they struggle to revisit. These aren't just entertainment choices anymore; they're emotional minefields that require careful navigation.

A man, single and between the ages of 35-44 hasn't listened to The Chainsmokers in four years. "That was my babe’s music," he said, referring to his ex-fiancée. "Every song reminds me of driving to her parents' house, of fighting in the car, of all the promises we made. I loved that music, but I can't separate it from her."

His response, I think, may reveal something crucial about how we organize our emotional lives. How we treat our own cultural history as evidence in a case we'd rather not reopen. The books, films, and songs that once meant everything to us become witnesses to versions of ourselves we'd prefer to forget.

But here's the thing, and there's a chance I'm probably overanalyzing this(like a number of people have already quoted on Twitter) but, if we cannot bear to revisit The Chainsmokers because it reminds us of our ex, how can we bear to stay with David or Lola, when our relationship hits its first real rough patch? If we've trained ourselves to avoid the emotional complexity of returning to familiar stories, we may be simultaneously training ourselves to avoid the emotional complexity of deepening existing bonds.

Don't take my word for it, the survey data supports this connection as well. Roughly 68% of non-rewatchers mentioned some form of emotional avoidance: memories that hurt, former selves they’ve outgrown, scenes that “bring too much back.” Those who avoid rewatching were significantly more likely to describe themselves as emotionally distant in relationships. They'd developed what might be called a psyche wary of return—one that has learned to equate depth with danger, familiarity with vulnerability, and commitment with emotional risk.

II.

Can repetition threaten emotional safety? Repetition says: feel again. And in a world full of many distractions and the facade of newer things, feeling again may be subversive. What does this little exercise reveal concerning the topic of repetition?

For emotionally distant individuals, repetition feels like regression. 37% of respondents reported emotional distance in relationships, and among them, the majority were also avoiders of favorite media. One wrote: “I find new things safer. The past holds too much weight.”

I asked the respondents; “Do you believe your emotional connection to the media reflects how you relate to people? Why or why not?”

Respondent A(random):

Yes; consumed content tends to impact my emotions whether positively or negatively. However, I personally feel media I enjoy has a greater impact as I like to avoid content that stirs up negative feelings within. Music I love calms me and that puts me in a good mood, so I’ll relate with people better. I purposely put on a good playlist to uplift my spirits. A good show/ film makes me want to show it to all my loved ones so they can tell me what they think about it, and even better if we can watch it together and I get to see their reactions. I feel it brings me closer to the people I love. I avoid any media that evokes negative feelings and try to mute content around said subjects.

Respondent B:

Honestly, I just fixate on things for a short time because it scratches a specific itch and then forget about it forever.

240 respondents(59% of the total), rewatch primarily for emotional comfort, nostalgia, or feeling-processing, and many of them described feeling almost ashamed of this need.

"I've reread Purple Hibiscus maybe fifty times,"A female, 18-24, admitted, "but my friends are always telling me to read other stuff. Even sometimes I don't read the BOTM from my book club and just go back. It feels too intimate now, so I don't really talk about it anymore.”

This “almost shame” around repetition speaks to a deeper cultural message - that emotional dependence is weakness, that needing the same comfort repeatedly is somehow failure. We've internalized the consumer culture's demand for novelty so completely that we've begun to pathologize our most human impulses.

The paradox here is profound, I tell you. Traditional psychology tells us that familiarity breeds contempt, but contemporary reality suggests something more complex; familiarity breeds intimacy, and intimacy requires vulnerability we may not be prepared to offer.

When we rewatch The Avatar or reread The Stormlight Archives, we're not just consuming content—we're entering into a relationship. We're allowing these stories to know us, to see us in our various states of being across time. For those who've built their emotional lives around safety, this kind of sustained vulnerability feels dangerous.

When you recommend a series or a show to your friend, more often than not, they will ask you, “how many seasons?” To ascertain if they are “ready” for whatever form of commitment this show will require. “What's it about?” “Is it sad?” Most people will say it's just a time issue, but is it really? I mean, no one is saying you have to complete it today, or tomorrow or even in the next year, so why not just start? The reason in there, reflects an emotional rhythm. Now, if your friend says they cannot watch the show because it's 7 seasons long, it does not necessarily mean they “cannot” commit, perhaps it means it is harder for them to “recommit.” Again, don't take my word for it. Of the over 210 respondents who claim they often rewatch shows and reread books, 60% of them claim they invest deeply in emotional relationships. Also, out of the 271 people who cited that they’ve had relationships that lasted for more than a year, 81% of them happen to be rewatchers. These are the kind of people that often find it harder to recommit due to greater investment in former or current relationships.

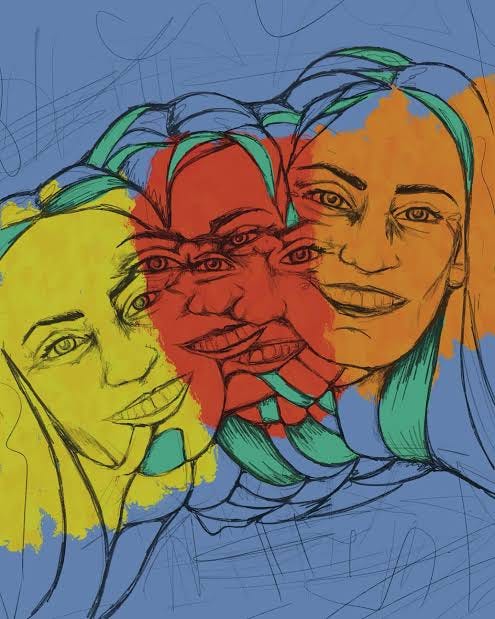

The survey revealed that 310 respondents—76% of the total—use media as emotional proxies or anchors.

But there's a crucial distinction between those who use media as a bridge to their own emotions and those who use it as a fortress against them.

Consider another male respondent, a 35-44 year-old, who mentioned he watches The Office every night before bed. "It's like a security blanket," he said. "I don't have to think about my day or my problems. I can just disappear into something safe."

He further wrote, "New episodes would require attention. I need something I can not-watch, you know? Something that will just wash over me."

I think this good man represents one side of the repetition spectrum; those who use familiar media as emotional Novocain. But there's another group, exemplified by another woman, age range of 25-34, who rewatches Little Women every December.

"I discover something new every time," she explained. "Last year, I noticed how Jo's relationship with her writing changes throughout the story. The year before, I was focused on the sisters' different approaches to love. It's like visiting an old friend who still has stories to tell."

The difference between both submissions, if checked carefully, isn't just in how they consume media, it's more about how they approach emotional life generally. The man uses repetition to avoid feeling; the woman uses it to feel more deeply. He has built a fortress of surfaces; She has maintained her capacity for emotional archaeology.

The survey data reflected this divide. Those who rewatch for comfort but avoid emotional engagement were more likely to describe themselves as relationship-avoidant. Those who rewatch for emotional processing and discovery were more likely to report relationship satisfaction and emotional intimacy.

III.

"There's always something new to watch. Why would I rewatch something when I could be discovering something amazing?"

This sentiment, expressed by dozens of respondents, reveals the third force shaping our relationship with commitment: the paralysis of infinite/hyper choice. We live in an unprecedented moment in human history. Netflix alone offers more than 15,000 titles. Amazon Prime adds thousands more. Hulu, Disney+, HBO Max, Apple TV+, the options are literally endless. But the promise of infinite choice has delivered something unexpected; like a new form of poverty. We have access to more stories, more music, more perspectives than any generation in human history, yet we seem increasingly unable to let any of it truly touch us.

"I can't even finish most of the shows I start," admitted a single, male respondent, "I'll be three episodes in and already wondering if there's something better I should be watching. It's like I'm constantly afraid of missing out on the perfect show."

His experience reflects what psychologists call "maximizer" behavior, a compulsive need to find the absolute best option rather than settling for something good enough. But this maximizing instinct, when applied to emotional life, develops an interesting antimony i.e. the search for the perfect experience then prevents us from having any deep experiences at all.

Think about how our grandparents consumed media and how we do. They might have owned fifty books and read each one multiple times. They might have seen the same movie in theaters twice, then again on television, then again with their children. This repetition was no limitation, but a relationship. Each return revealed new layers, new connections, new meanings. We, by contrast, live in an age of infinite choice and diminishing returns. We consume voraciously and digest little. We're cultural tourists, always moving, never settling, never allowing ourselves the luxury of true familiarity.

The streaming revolution serves as a perfect metaphor for this broader cultural shift. We've moved from a culture of scarcity, where owning a few albums meant listening to them deeply to a culture of abundance that paradoxically produces emotional poverty.

This tyranny of choice extends beyond media consumption into every aspect of our emotional lives. Dating apps present us with infinite romantic possibilities, creating the same paralysis we experience scrolling through Netflix. Social media shows us curated versions of countless lives we might be living. Career platforms present endless professional possibilities. We've become a culture of perpetual window shopping, always wondering if there's something better just a swipe away.

The survey data revealed a stark correlation:

44% of respondents confessed to “getting bored easily.” Among them, media repetition was almost nonexistent. And is it not also interesting that out of 410 adult respondents, 67.8% are single and 6.3% say “it's complicated?” The survey will further reveal a lower rate of sustained relationships as 31.9% have had relationships that lasted for less than a month and another 44.6% between 2-6 months. Only 9.6% of total respondents have had relationships that lasted for more than 2 years.

Our minds are overstimulated and mostly under-attached. With endless content comes a subtle fatigue, a flattening of emotional stakes. If nothing is special for long, nothing can be sacred.

Hyperchoice does not just change how we consume. It may, in fact, alter what we value.

IV.

"I need constant stimulation. If I'm not consuming something new, I feel anxious."

This particular submission illuminates one—and perhaps the most crucial—factor shaping our relationship with commitment: we've literally rewired our brains for novelty‑seeking. Neuroscience shows that novelty‑seeking is driven by specific brain circuits (e.g., zona incerta, ventral striatum) that motivate exploration independent of immediate rewards ([Her Campus][1], [neuroscience.wustl.edu][2]).

The human brain, in its beautiful plasticity, adapts to the patterns we feed it. When we train ourselves to constantly seek novelty, we strengthen neural pathways that crave stimulation over satisfaction, breadth over depth, conquest over cultivation. This highlights that our brains are experience‑dependent, rewiring synaptic connections in response to repeated stimuli—a foundational concept in neuroplasticity .

We become neurologically adapted to a culture of disposal, where the solution to any form of dissatisfaction is replacement rather than repair. While dopamine release in response to new stimuli is adaptive, it can predispose us toward novelty‑seeking behaviors at the expense of depth and commitment .

But this isn't just about dopamine hits and shortened attention spans. Something more profound is happening. We're losing what I call our "return muscles"—the neural pathways that allow us to find new meaning in familiar experiences, to deepen rather than simply accumulate. Studies on the “mere exposure” effect and familiarity show that repeated exposure to stimuli (e.g., music, media, people) strengthens liking and emotional response via perceptual fluency and neural reinforcement involving frontal and limbic circuits ([Wikipedia][3]).

The survey data supports this theory. 76% of respondents said they use media as emotional proxies—books, songs, and shows that stand in for feelings they struggle to express. But for some, this is not intimacy. It’s outsourcing.

A respondent wrote, “I let music cry for me.” Another wrote: “Movies teach me how to feel.”

That reads like delegation to me.

And the more we outsource, the harder it becomes to rewatch. Because repetition demands not just attention, but emotional memory—and memory, like love, asks for vulnerability.

A 2024 psychology thesis also found that familiarity in binge‑watching correlated with reduced depression and implied deeper emotional engagement, suggesting that those who avoid familiarity might also be emotionally distant.

Consider the neurological implications. When we rewatch a favorite scene from a beloved film, specific neural networks activate—typically involving auditory, motor, and emotion-related regions . These same networks are involved in long‑term relationship satisfaction, helping us discover new layers in people we know well ([Her Campus][1]).

But when we train ourselves to always seek novelty, we're simultaneously training ourselves to abandon things before they can reveal their full depth. We're becoming neurologically unsuited for the patient work of long‑term commitment. Without frequent reinforcement of familiarity pathways, the balance tips toward novelty—leaving less neural bandwidth for sustained depth.

Dr. Anna Lembke, a psychiatrist at Stanford, has written extensively about how our brains adapt to constant stimulation. “We’ve turned our brains into dopamine slot machines,” she explains. “We need increasingly intense stimulation to feel satisfied, which makes us less capable of finding meaning in ordinary experiences” (Lembke, 2021). Although primarily clinical, her work aligns with findings on how escalated stimulation reduces the appeal of familiarity and ordinary rewards.

This has profound implications for our relationships. Love, in its deepest sense, is about returning—to the same person, through different phases of life, finding new depths in familiar intimacy. But if we've rewired our brains to equate familiarity with boredom, we've made ourselves neurologically unsuited for the work of long‑term commitment. Repeated stimuli activate networks that foster emotional regulation and resilience—key elements in maintaining commitment ([Cambridge University Press][4]).

The survey revealed that people who regularly rewatch media were more likely to describe themselves as emotionally present in relationships. You say it's coincidence, I say it's consequence. The neural pathways that allow us to find new meaning in familiar stories are the same pathways that allow us to find new depths in familiar people.

What 410 People Told Me About Love

The Swedish concept of "lagom"—meaning "just the right amount," offers a useful framework for understanding what we may have lost in this world of plenty. Truly, a lot of personal reflections from this assessment stuck with me and were deeply reflective. I honestly wish I could share everything.

Two different, yet equally profound responses I’d like to share, regardless; came from a man, who described himself as a "content completionist" that is, he is always seeking the next show, the next book, the next experience and the other respondent, a lady who said she's watched The Godfather trilogy every year for the past 15 years.

"I notice different things each time," she explained. "When I was younger, I focused on the violence and the power. In my twenties, I started seeing the family dynamics. Now, in my thirties, I'm drawn to the quiet moments, the way silence works in those films. It's like visiting a place you know well but seeing it with new eyes."

The man, by contrast, described a constant state of cultural FOMO. "I keep a spreadsheet of shows I want to watch," he said. "There are currently 247 entries. I feel like I'm falling behind, like I'm missing out on conversations, like I'm not keeping up with culture."

The survey data revealed that lady’s approach to media consumption correlated with relationship satisfaction and emotional intimacy. The man's approach correlated with relationship anxiety and emotional distance. The capacity to find new meaning in familiar experiences, it turns out, is inseparable from the capacity to find new depths in familiar people.

Now, here's the most interesting part about this man’s statement: “But now I’ve started deliberately rewatching one film each month. It's changed how I see everything, I believe.”

From my observation, I believe he noticed his own patterns of novelty-seeking and decided to experiment with intentional repetition. He now represents a small but growing movement of people who are beginning to question the culture of endless consumption.

"I realized I was treating movies like I was treating everything else in my life," he further explained.

As a typical cinephile myself, I understand how heavy it is to always want to immerse yourself in every movie experience. At some point, I stopped allowing myself to go deep. I was culturally bulimic—consuming everything and digesting nothing. I could barely remember characters or scenes, I was merely watching to log on my Letterboxd.

The man's practice is simple but radical: once a month, instead of watching something new, he returns to a film he's seen before. He takes notes, pays attention to details he missed, allows himself to be surprised by the familiar.

"Last month, I rewatched Her," he said. "I've seen it maybe four times, but this time I noticed how the cinematography reflects the main character's emotional state. The framing gets tighter as he becomes more isolated, more open as he learns to connect. I'd never seen that before."

His experience now reflects what researchers call "the paradox of choice reversal"—the counterintuitive finding that constraints can actually increase satisfaction. By choosing to limit his options, he'd discovered new possibilities within those limitations. Perhaps deliberate constraints may then teach us how to love better in our era of infinite distractions.

The survey revealed that respondents who had developed similar practices—“deliberately” returning to familiar media—reported higher levels of relationship satisfaction and emotional engagement. They'd perhaps learned to see commitment not as limitation but as a form of creative constraint that opens up possibilities rather than closing them down.

My most important takeaway is the “faith renewal,” that many of the personal reflections offered me. That depth is possible, and very much alive. That beneath the surface of familiar experiences lie endless layers of meaning, that the well of any truly great work of art is bottomless. That includes You and I.

And maybe, just maybe, the capacity to return is truly, the capacity to love.

Results & Conclusion

Needless to say, what has now emerged from this research isn't just a portrait of individual psychological patterns but a map of a broader cultural transformation. We're witnessing the emergence of what might be called "commitment culture"—a way of organizing social life around the avoidance of sustained emotional engagement.

We see it in our job-hopping careers, our nomadic living patterns, our tendency to abandon social groups when they become complicated, our preference for online communities that we can exit at will. Our disdain for accountability, and well… the modern problem of always finding a quote that justifies everything.

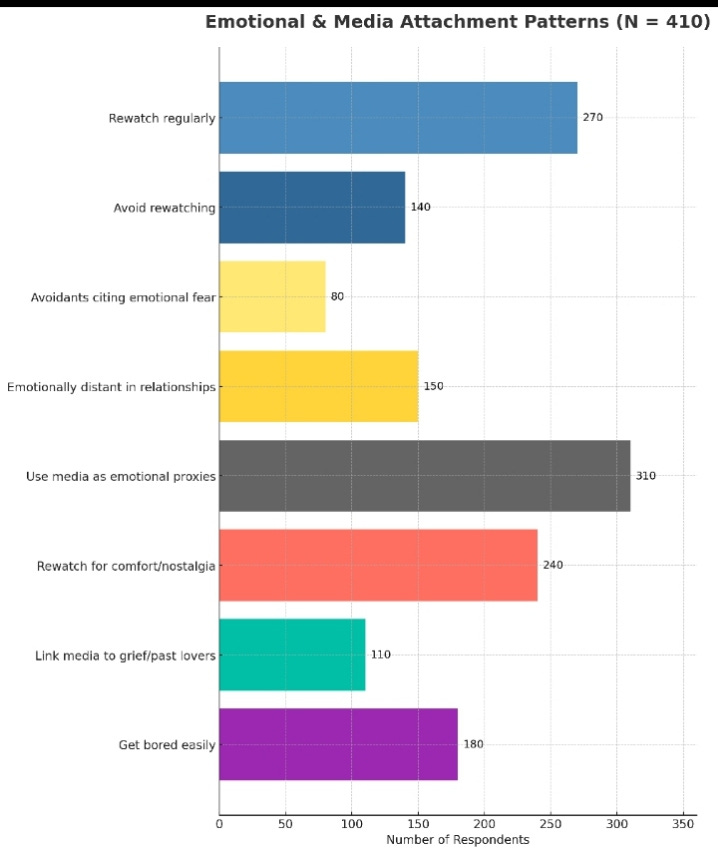

Here is the Results section visualized: a summarized, horizontal bar chart showing how respondents align across emotional tendencies and media behaviors.

From the survey of 410 individuals, we observed several overlapping tendencies:

270 respondents (66%) rewatch or reread media regularly.

140 respondents (34%) avoid rewatching, with 80 of them (20% of total) citing emotional discomfort or fear as their reason.

150 respondents (37%) described themselves as emotionally distant in relationships.

A significant 310 respondents (76%) use media (books, films, or music) as emotional proxies or anchors.

240 individuals (59%) rewatch primarily for emotional comfort, nostalgia, or feeling-processing.

110 respondents (27%) explicitly associated their favorite media with past lovers, grief, or phases of life they struggle to revisit.

180 individuals (44%) identified themselves as easily bored—often correlating with a preference for novelty over repetition.

This data reinforces the essay’s central thesis: emotional repetition in art reflects emotional rhythms in life. The avoidance of aesthetic return often parallels a desire to avoid re-encountering vulnerable emotional states—a pattern that may be as modern as it is ancient.

Thank you for reading.

Key References

Novelty‑seeking circuitry and dopamine dynamics ([neuroscience.wustl.edu][2])

Neuroplasticity driving familiarity strengthening ([NeuroLaunch.com][5])

Mere exposure effect and repeated media engagement ([frontiersin.org][6])

Emotional benefits tied to familiarity and rewatching  Neural overlap in media familiarity and relationship satisfaction ([link.springer.com][7])

Lembke, A. (2021) Dopamine Nation: Finding Balance in the Age of Indulgence. New York: Dutton.

Note: Due to respondents choice of anonymity, and substack’s email limit, It was impossible to share all of the results. But if you want some other questions answered, please notify me in the comments or send me a mail. Thank you.

I've always thought the problem was a lack of sound training in art criticsm. Skepticsm is often the first approach to art before indulgence, for most people. Despite this, they eventually develop some familiarity, but often with a select few genres/with, and rarely with any specific members of said categories. Resultantly, they shut their minds to anything outside selected favorites while still in search of novelty. And at this point art exists only to serve some shallow need, and this is good for artists who only create to satisfy, but not for artists who create to reveal new phenomena or examine/express old ones in fresh perspective. Their work is easily waved away when met with that first round of skepticsm, probably only to be remembered long after they're dead and their work finds new ownership in the public domain.

Coupled with emotional cultivation, there's an additional possibility that the majority of people are poor critics of art, and will yet critique because they have to consume, is what I'm saying.

This piece hit hard, especially in a world where consumerism quietly shapes how we love. We don’t just feel anymore; we evaluate, compare, and scroll past.

In a culture addicted to upgrades and instant highs, maybe commitment is our most radical act.

Thank you for writing this; it truly is reflective and deeply touching. Also, well-done on the real-time data!