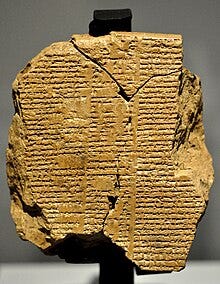

Five thousand years ago, The Sumerians etched cuneiform scripts into clay tablets. Their writings recorded grain supplies, legal codes, and prayers to gods who were both feared and revered. The unpredictability of floods, famine, and disease was omnipresent. Writing became a means of control, a way to catalog and structure the unmanageable forces of the world. To write, even then, was to assert mastery over the ephemeral. The things we do not really understand. The chaos.

The Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the earliest known works of literature, transforms this unpredictability of mortality into a story of heroism and loss. By giving narrative shape to chaos, the Sumerians began a tradition that persists to this day. Every writer, knowingly or not, engages in this tradition, trying to make sense of the unpredictable forces that controls us. Love, grief, nostalgia, pain—whatever the emotion, they strive to render themselves into the fabric of our consciousness, as if to declare their permanence. They do not merely exist; they seek articulation, a form. They yearn to be rendered visible, to escape the ineffable and take shape in words, images, and metaphors.

Chaos surrounded the French Revolution. The upheaval of monarchy, the rise of radicalism, and the guillotine’s unrelenting rhythm tore apart the social fabric of France. Amid this disarray, it didn't stop painters from painting, nor did it stop storytellers from telling. It definitely didn't stop writers like Edmund Burke and Mary Wollstonecraft from taking to the page, while attempting to impose order on this chaos.

Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France saw the events as a catastrophic break from tradition. It is, therefore, not a surprise that Burke’s rhetoric is laden with the use of metaphor. He also said that society is a fabric fashioned over centuries and a call for dismantling this fabric in the name of principles, was folly. Society is indeed a contract,” Burke wrote, “but the state… is a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.” In framing the revolution as a reckless severing of this eternal contract, Burke gave shape to the chaos, he transformed it into a narrative of hubris and ruin, and his writing became a bulwark against the storm—a means of asserting order in a world that seemed to be spiraling out of control.

To the discerning reader, Mary Wollstonecraft’s name may evoke familiarity—or perhaps not. For those unacquainted, allow me the pleasure of introduction. Wollstonecraft was a formidable writer and an extraordinary woman of her age. Her pen wielded considerable influence, particularly in shaping the nascent ideals of feminism. Among her many profound contributions, the one I hold in highest regard is her visionary advocacy for a social order rooted in reason. Mary would go on to address Burke's reflections concerning the French Revolution.

Mary Wollstonecraft viewed the French Revolution as a necessary disturbance, not a failure. Her A Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790), which was written to reply to Burke, essayed a brilliant rebuttal of Burke’s celebration of conservatism, and offered a passionated call for forward movement and egalitarianism. For Wollstonecraft, any disorder caused by revolution was not a sign of decadence but of regeneration: It was a painful yet necessary process which was aimed to destroy all the unjust structures to give the new, fair society a start. Wollstonecraft was not less hot-headed than Burke as a writer; it is just that her metaphors were of blossoming and freedom. She used the words of revolution as a sort of purging; the winds of change that blow away the spoils of tyranny for the benefit of the earth for new ideas.

To Mary, Burke's reverence for tradition is no true order; it is a hollow façade that fails to confront the glaring inequities at the heart of society. To her, his logic is not merely unconvincing—it is antithetical to justice. This divergence is where I try to encapsulate the uniqueness of every writer’s lens. Though we may encounter the same chaos, the way we interpret and frame it defines us. It is in this act of reckoning with disorder I believe, that a writer’s voice is forged—distinct, unrepeatable, and wholly their own.

And if you were to ask me, “How might I write well?” my immediate response would likely be pragmatic: read extensively, practice diligently. But if you ask me on a deeper level, I would caution you that such advice pertains merely to the mechanics of writing—to its formalities. True writing, however, is profoundly intimate. It demands a personal acquaintance with the turbulence of your own mind, the discordant symphony of thoughts— the one that clamours for attention, vying to be heard. The blank page is both an invitation and a challenge: can you distill this storm into coherence?

Let me even take you back to my primary school days, when I first dabbled in the fine art of writing. Truth be told, I wasn't the only one struggling to make sense of the chaos in my mind—my attempts at putting those thoughts to paper were equally baffling. The words spilled out in a jumble of gibberish, a frenzied mess even by primary school standards. And don't even get me started on my handwriting—it was a crime against legibility. Despite the illegible scrawl that would have made any eyes recoil in horror, I kept on. I was awed by the likes of Achebe and Amos Tutùolá, and yet, my attempts were like the one of a palmwine drinkard, the more I tried, the more things fell apart. A classic case of what I ordered vs what I got.

The process will often feel Sisyphean. You write, revise, and rewrite, only to find that the chaos has shifted, morphed into something new. Yet, like Sisyphus, you persist. You have to.

The only way most of the time I suspect we get these metaphors is through the experience and understanding of chaos and writing is the refining fire. Consider Shakespeare’s Macbeth here, where the destabilization of order caused by the ambition is figured in terms of a storm. Or Dickinson where dying is like taking a carriage ride, official and planned. Where metaphors don’t eradicate upheaval, they displace it and redirect it into comprehensible entities; anchor points in the tempest.

But I must warn you now, there is danger in this desire for order. Too much structure can suffocate. Writers, like scientists or philosophers, risk oversimplifying, flattening the richness of chaos into something too neat, too sterile. Not all chaos is meant to be understood. Some of it, as Nietzsche suggested, must be danced with. In writing, this balance is delicate. The writer must neither impose too rigid a framework nor let the chaos spill uncontrollably onto the page. Great writing often lives in the tension between the two—structured enough to be coherent, chaotic enough to feel alive.

And perhaps this is why we write: not to vanquish chaos, but to commune with it. Writing does not quell the storm; it offers us a sanctuary—a quiet refuge where we may ponder, interpret, and distill meaning from the cacophony. Whether we are documenting the annals of history, weaving the threads of fiction, or inscribing the depths of our innermost thoughts, we partake in an innately human endeavour: the yearning to render chaos intelligible, to etch a map of our passage through its labyrinth.

Thus, we must write. We must inscribe our marks upon the ever-shifting sands, fully aware of their impermanence yet steadfast in the belief that their transience holds significance. It is an act imbued with audacity, ingenuity, and an unyielding hope. In the realm of writing, as in the unfolding of life itself, chaos is no adversary—it must be our inspiration, it must be our inexhaustible muse.

Your essays are the best thing that has happened to me for now. More about distilling the chaos into coherence, please🤲

I have written on Medium and used your words as a guiding light. Thank you, Adé Adé.