The first time Fọlá heard about a "freelance opportunity," he was standing in line at a bank, sweating in the heat of a slow afternoon. The offer came from an old friend, Ikenna, who sent a voice note laced with the casual confidence of someone who had long figured life out.

"Bro, it’s easy money. Just sign up, complete tasks, and they pay in dollars."

Easy money? Fọlá had long learned that nothing about money was easy, but hunger had a way of making even a skeptic believe. Make I try am na.

The contract arrived in his inbox the next morning, dense with legalese, the kind of text that felt like a trap but was too exhausting to decipher. He scrolled straight to the bottom and clicked "Accept."

The first few weeks were bliss. The work was mindless - rewriting ads, answering customer queries, clicking through surveys that didn’t seem to matter. The money trickled in, enough to keep his phone data on, enough to eat. A win.

Then, the changes came.

The tasks grew longer, the deadlines shorter. The payment structure shifted, bonuses removed, fees deducted for "system maintenance." He tried to contact support, but the responses were vague, circular.

"Dear Fọlá, our terms of service are dynamic and subject to change. Please refer to the contract for details."

He scrolled back to the document he had once ignored, and there it was, buried in Section 17, Clause 4: "By accepting this contract, you agree to any future modifications as deemed necessary by the company."

Any future modifications.

His hours doubled. He was working in his sleep, in his dreams. The more he worked, the more he owed - fees for withdrawal, penalties for delays. It was a machine, and he was its fuel.

One night, exhausted, he messaged Ikenna. "Bro, how do you get out?"

Ikenna replied with two laughing emojis.

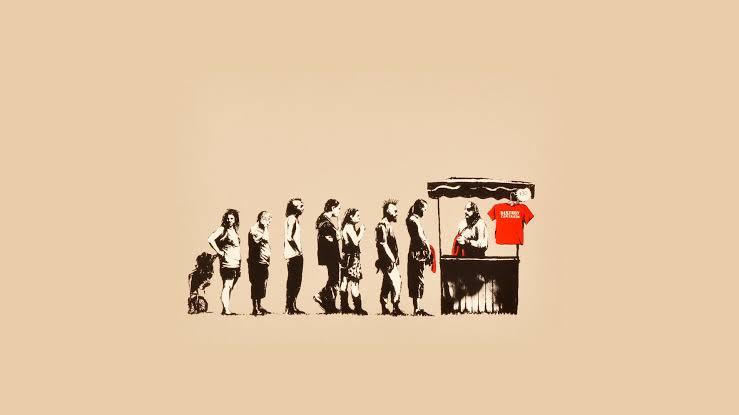

Every morning, billions rise at the command of a clock they themselves have wound. They drape themselves in fabrics they purchased, march to occupations they may have selected(though who can say with certainty?) They exchange their wages for coffee, glide their fingers over plastic to summon invisible currency, and let their thoughts be auctioned off to merchants who know their desires better than they do. They click "Accept" on unread contracts, believing, with a peculiar faith, that they have chosen. L-O-L.

You may not be aware, but capitalism has perfected a certain paradox: freedom without autonomy, consent without power.

Under capitalism, we are told that consent is the sacred principle of all transactions. The worker consents to his wage, the consumer consents to the price, the company consents to its contracts. But let us examine this marvel more closely. When the alternative to consent is destitution, when refusing a wage means starvation, when declining a contract means oblivion, can we still call it consent? Does the sailor, thrown into the sea, "consent" to swim?

And you know, Defenders on Twitter will say, "No one forces him to work for such a wage, no one compels him to make such a purchase!" And yet, if a man accepts his chains only because the guillotine stands behind him, shall we call him free?

Consent in my understanding, implies an ability to meaningfully say "no" without severe consequences. But also, capitalism ensures that for most people, refusal is not an option, perhaps only a fantasy.

Capitalism prides itself on the "freedom" to choose employment. You dislike your job? Okay, quit. Are you underpaid? Demand more. You want better benefits? Please negotiate.

But what happens when the alternative is poverty?

Is it truly freedom when workers must choose between exploitation and starvation?

This is simply the silent coercion of capitalism. It operates without shackles, yet the weight of economic necessity binds us tighter than any chain.

The gig economy was once heralded as a revolution in labour freedom. They say workers could be their own bosses, set their own hours, and escape the tyranny of the traditional workplace. Yet, in practice, gig workers are paid pennies per delivery, with no healthcare, no pension, and no labour protections. Illusion of choice.

Platforms like Uber, InDrive and Bolt thrive on the myth of consent. Workers technically choose to accept each ride, but when rent is due, the choice is but a mirage. Now, you may interject - "But Uber drivers earn a decent living!" My dear optimist, how charmingly mistaken you are! Like all defenses of capitalism, this one is also built on sand. What appears to be a fair wage is nothing but a magician’s trick, where the rabbit disappears and only the top hat remains.

In Nigeria: The Bolt driver, for example, provides the car, pays for the fuel, suffers the wear and tear, endures the price of inflation, handles his own insurance, and braves the whims of a market that grants him neither stability nor respect. Meanwhile, the company, shining, untouchable, unbothered - takes its generous cut and bears no burden. The driver is independent, yes, but only in name, much like a sailor cast adrift and congratulated for his freedom to swim.

This, dear reader, is capitalism in its purest form: profits hoarded at the top, risks dumped onto the worker. And if you wish to witness its cruelty in real-time, simply order a ride and spend an extra ten minutes haggling with a desperate driver over a base fare that would hardly buy you breakfast today.

The same applies to your corporate jobs. Employers demand unpaid overtime, unreachable KPIs, and emotional exhaustion. The alternative? Find another job in an economy where companies are downsizing and AI is replacing human labour. Whew. I mean, it's only been a few days since OpenAI rolled out that anime model(I'm not sure of that name, I don't wanna sound racist either. I'm sure you’ve seen them), and creators have been on a rant spree since then.

When "no" means homelessness, is "yes" a choice?

I don't like capitalism, so I work for free. Be like me.

Capitalism does not ask for permission; it assumes compliance.

Tell me, when was the last time you truly agreed to have your data harvested? You didn't. You merely clicked "Accept All Cookies" to remove a pop-up window. Have you noticed they don't even give you an option to decline these days? There. You either accept or get out.

Big Tech—Google, Facebook, Amazon, Pornhub perhaps also, collects, stores, and sells your information without explicit consent. Hm. They argue that users agree to their policies, but can consent be meaningful when the only alternative is total digital isolation? Is it consent when you know I'm desperate? I'm just here to see a video, what do you need my card details for?

This extends beyond technology, by the way. From microtransactions in video games to hidden fees in banking, corporations build business models on the assumption that consumers will not read the fine print.

And when they do?

The response is always the same: "You agreed."

You agreed when you used the free trial.

You agreed when you didn’t cancel on time.

You agreed when you scrolled past the 17-page Terms of Service. 17 pages? C’mon now.

And they will not be wrong either, at least, not legally. In capitalism, silence is consent, and ignorance is compliance.

Nowhere is the illusion of consent more evident than in the exploitation of the poor.

When a single mother in Bangladesh works for $2 a day in a sweatshop, did she consent to those wages? When a child in the Congo mines cobalt for smartphone batteries, did he truly agree?

The defenders of capitalism will argue: No one forced them.

But doesn't economic desperation forces decisions as surely as a gun to the head?

What capitalism does best is to create conditions so dire that people will willingly accept exploitation, then declare it a choice.

“They could leave.”

“They could do something else.”

But the world is built in such a way that they cannot. Can they?

And so, sweatshops, child labour, and unethical sourcing continue - not through outright slavery, but through an economic system that makes slavery unnecessary.

You see, it does not simply force you to work, no. It convinces you that your work defines you. It does not only make you buy things; it makes you believe that your purchases are reflections of your identity.

"You don’t just need a phone, you need this phone."

"You don’t just want a career, you need a passion."

"You don’t just work, you grind."

What makes capitalism uniquely insidious is that it does not impose control from above. It plants its directives deep within our psyche until we want what it wants for us.

The most controversial applications of capitalist consent perhaps lie in the commodification of the body itself.

Sex work has been rebranded as "empowerment" in some circles, with the argument that women (and men) should be free to sell their bodies if they so choose. And yet, the vast majority of sex workers are in the industry not by empowered choice, but simply by economic necessity.

When economic necessity dictates the terms of survival, is it truly autonomy or just the illusion of it? What makes a sex worker negotiate and sometimes decline if you don't give them what they want? If it was simply a “choice,” why not just take any amount? Perhaps as compensation for a well adorned hobby.

I believe to call it empowerment is to ignore the harsh reality that most enter the trade not from desire, but from desperation, shaped by poverty, systemic inequality, and a lack of viable alternatives. A decision made under duress is not freedom; it is coercion wrapped in rhetoric.

Beyond the financial constraints, there are deeper forces at play - violence, exploitation, and power imbalances that strip agency rather than affirm it. If empowerment means having the freedom to choose without the weight of economic despair, then what we call empowerment here is merely survival in disguise. True liberation would not be found in normalizing the commodification of bodies, but in dismantling the conditions that make such a choice feel inevitable.

Likewise, the global organ trade flourishes because the poor are willing to sell their kidneys to the highest bidder. But what does willing mean when a person must sell a body part to afford a house?

A starving man does not choose to steal bread; he is compelled by forces greater than law or morality, the brute force of hunger itself. In the same way, the desperate do not choose to auction off their flesh; they are cornered by the cold arithmetic of survival. We call it a market, but what is a market where one man bargains with coin and another with his own flesh? It is not trade; it is coercion dressed in contract law.

Capitalism, in its most brutal form, does not outlaw desperation, it monetizes it. The poor man’s kidney is not worth less because it beats in his chest; it is worth less because he owns it. But let that same organ pass through the hands of a middleman, a hospital, an insurance company, and suddenly it is no longer the price of rent, it is the price of a yacht. This is not economics; it is the careful, calculated alchemy of turning human suffering into profit.

And so, the question remains: If willingness is measured in degrees of desperation, at what point does free will become nothing more than the absence of alternatives?

One of capitalism’s most seductive illusions is the promise of upward mobility. The idea that even the lowest peasant may, with toil and virtue, ascend to the ranks of the mighty. But in a world where wealth flows ever upward and the gates of privilege are locked from within, does this fairy tale withstand scrutiny?

Look at this simple statistic: the richest 1% possess more than the bottom 50% combined. Wages for the labouring multitude stagnate, while the lords of finance multiply their fortunes without lifting a finger. The worker toils; the speculator feasts. And yet, capitalism demands our devotion, not through justice, but through anecdote. It parades before us the miraculous exceptions: the beggar who became a king, the clerk who became an emperor of industry. These rare ascents serve not as proof of fairness, but as dazzling spectacles to keep the masses hopeful, obedient, and forever chasing a dream that remains just out of reach.

Then they try to feign empathy. Capitalism, they assure us, is imperfect, like a lover who is faithless but at least comes home at night. It may not be good, but it is better than the alternatives, they insist, as if we were all born with the sacred duty of choosing between two evils.

Observe the cunning of this argument: capitalism is never weighed against what has not yet been imagined. No, it is always compared to the ghosts of fallen empires, to regimes that crumbled under their own excesses. This is akin to declaring that a disease is preferable to its worst cures, while refusing to search for health itself.

But must we bow to this reasoning?

A system that buys and sells all things - knowledge, love, even dignity, cannot be the pinnacle of human progress. A system that rewards the clever manipulator over the honest labourer, the speculator over the creator, cannot be the final arrangement of mankind. I refuse to accept that.

And yet, capitalism has performed its greatest trick: it has convinced its subjects that it is eternal.

We do not endure it because it is just.

We endure it because we have been told there is no escape.

This is a brilliant work and I understand that because it is a critique, the harshness of its tone, and the action of digging out the most rotten side of the underbelly of capitalism, its ugliness, is actually its intention, but as all other critiques of capitalism, as the multitudes that they are, it does little to tell you why the system still exists and why many of the alternatives fail. It talks of the ugliness whilst its beauty is disregarded. But I understand. It is a critique after all and you did hit the spot.

You brought up three major focal points in this essay that capitalism's flaws seem to hover around. One of it is the illusion of choice and consent. The system tells you that you have a choice whilst at the other end of the choice is a life of poverty. If you are not working, you are dying. This is a good point if only it was really never just an issue of Capitalism alone, and we've always gambled with these choices before capitalism. A person would eat regardless and if they are not going to be slaving their way out in a job, they would be in a farm, or in a forest hunting. The superiority capitalism has in comparison to the others is that atleast in a job, you are sure to be getting paid and your employer owes you that. In the others there are fat chances that something bad will happen to your crops and or you will not come back with a catch in hand.

Now I understand we do not have to live in either way. We could think of a better way for a person to say "I don't want to work for pay" and yet not die. There are problems with this for sure. People do have to be working to keep a society afloat and to be honest with you, capitalism is not the first master to give you the "who doesn't work cannot not eat" maxim. Life gave the necessity for that first. Capitalism just turned that necessity into profit. The question is who would work for other people to just sit down and not do anything? What if everyone decides that they will not work since the state is arranged in that manner?

You can see that unless we build machines to solve this working problem, it would continuously stick to our faces like glue. However this will not be any different from capitalism. It's capitalism, just with machines as bots. This brings me to another critique I usually throw at critiques such as yours. Your use of the term Capitalism gives little space for a nuanced understanding of the problem. You throw the baby with the bathwater and my bro I tell you such mistakes have cost the lives of billions.

Secondly you criticized upward mobility. I am with you on this one. Many people don't get to become "bosses of their own" at all. But I also know that in better places like the USA as opposed to Nigeria upward mobility is much less a myth than it is here. In a functioning system, it does work. We might disagree on whether or not this is a problem of capitalism.

As for your last critique of the defenders of capitalism, which are folks like me, who tell you about failed system and how capitalism is the only efficient and perhaps working one; I will not try to tell you about the merits of capitalism since this comment has grown too long, but I will say that it is not a bad thing to wish for a better system. We should. However it is paramount that we watch our steps. Life is not very much as it seems sometimes.

A wonderful read