On Wondering and Wandering

Does the cat truly have nine lives, or is curiosity simply not brutal enough?

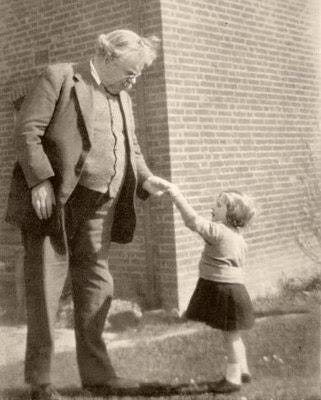

Consider the six-year-old. Not the six-year-old of pedagogical platitudes, but the six-year-old as the curious archetype. In my tribe, they call you Àgùnfọn. Thank goodness I wasn't born a cat, I’d probably be dead by now.

You see, there is no passion so misunderstood as curiosity, and no human trait so simultaneously trivial and tremendous. Literates today swear it is a virtue and promptly proceeds to kill it with the most deadly weapon known to intellectual life: systematic education. We send children to schools to be curious, and then spend every waking moment teaching them not to be. We give them maps and tell them to explore, and then draw thick red lines declaring where they must not step. We present the universe as a textbook to be memorized, when it is actually an adventure one must pursue. A tragedy(if you are curious enough to ask me).

Curiosity is no more a subject to be taught than love is a science to be dissected. It is a spirit, a flame, a divine madness that cannot be contained within classroom walls or academic journals. It is not a mere cognitive function. It is a metaphysical pirouette, a dance between what is known and what is possible. To be curious is to stand at the razor's edge between understanding and bewilderment, to feel the intellectual vertigo that makes lesser minds retreat and makes true explorers leap. When I have conversations about passion, I always advice curiosity. That delightful infection they tell you to treat. “Stop asking so many questions,” they say. But they forget, they forget that this sublime condition makes donkeys of scholars and children of sages.

To be curious is to be revolutionary. To ask 'why' is to challenge the entire edifice of received wisdom. The child who asks ‘why’ the sky is blue is performing a more radical act than most political philosophers achieve in a lifetime. Everyone wants to diagnose wonder, but few want to catch it.

“Seriousness is the last refuge of the unimaginative,” said Oscar Wilde. But curiosity? Curiosity is imagination's most mischievous ambassador. It sneaks past the border guards of established knowledge, carrying contraband questions that might just detonate entire paradigms.

I once asked my mother, “Where did I come from?” With a straight face and a glint of mischief, she replied, “You came out of my mouth.”

“Your mouth?” I shot back, my voice rising in disbelief. “How’s that even possible? What about your teeth? Did I roll out like an egg?” The room erupted in laughter—my mother, my family, everyone—but I couldn’t quite grasp the joke. Still, I did what any good child does: I joined in, chuckling along, though the mystery of my birth still disturbs me. There it was, the origin of my curious laughter.

I will further go on to press my teachers at school and church with endless questions. They hated it. "Must you know everything?" they would curiously inquire. When they choose to be less pejorative, they will hold your hands and tell you something like, “Sẹ́tọ̀, this thing is beyond your level.” Mr. Yahweh Gbàwá, is it beyond my level, or you do not know the answer? Nobody will beat you. They implied that these questions were dangerous and unnecessary. They were right—but not in the way they thought. The danger wasn’t to me; it was to them. These questions reminds me that what we know is infinitesimally smaller than what we do not know. Wrt my yearning, down to the repudiation experienced from the supposed knowledgeables, I understood then that certainty is truly, the last refuge of the intellectual coward.

Every time I sought answers, they laugh, they make jokes, or pooh-pooh me, as though I do not respect the careful fences erected between disciplines, between knowledge and mystery, between the gravity of adulthood and the whimsy of a child. I was taught to be gentle. To be careful, to tiptoe around the brittle egos of the learned. Now, I will admit that my tongue yielded, but my ears, keen and stubborn, did not. My eyes refused to be struck dumb. Curiosity is listening. It is watching.

The library will now become my sanctuary, a world apart. For hours, I would lose myself in the pages of the science encyclopedia and it was there that I discovered another truth: the truly great were never careful men or women. They were madmen, mystics, those who looked at the limits of human knowledge and saw not a wall, but an invitation. Columbus did not sail to prove the world was round; he sailed because the round world beckoned with a siren song of mystery. Darwin did not categorize species; he heard them whispering secrets. Marie Curie did not discover, she irradiated herself in pursuit of an invisible truth. Einstein did not calculate; he dreamed. These were not serious adults. These were wonderers, wanderers—professional questioners who refused to colour within the lines of received wisdom.

And perhaps intellectual vitality is one that must allow playfulness. That an individual may not be truly learned until he can make the most arcane subject perform a comedic somersault. A quantum physicist who cannot joke about Schrödinger's cat is less of a physicist, but more a glorified accountant of subatomic probabilities. A theologian who cannot find humor in the paradoxes of divine omniscience is merely a bureaucrat of the metaphysical. Perhaps. Curiosity must be playful. Play is the language of the unbounded.

One might object: "But curiosity can lead us astray! Not every question is worth asking!" To which I respond: every question is worth asking. Not every question deserves an answer, but every question deserves its moment in the interrogative sun. The moment we start policing questions is the moment intellectual tyranny begins.

Granular proficiency is the death of curiosity, fragmenting knowledge so completely that a neurobiologist and a poet might as well live on different planets. What we need is a new academic ritual—not the dry, stilted dissertation defense, but the Curiosity Roast. Let me explain better; a scholar must not only present their research they must make it sing, make it dance, they must lay bare its absurdities. Your quantum mechanics thesis? Make me laugh. Your sociological study? Tickle my intellect. If you cannot turn your expertise into a shared moment of wonder, then you are not much of a scholar, perhaps just a librarian of the dead.

A life of curiosity is an existential performance art—a profound, playful improvisation that makes reality itself lean in, listening for the punchline.

Curiosity is not a skill. It is not a method. It is a temperament. It is the radical openness that allows a human, be a child or an adult, to look at the most familiar object and see it as though for the first time. Let us not teach curiosity. Let us infect each other with it. Let us create environments where not-knowing is not a sin but a celebration. Where questions are not threats but invitations. Where learning is not a duty but a delirious adventure. Let us look at the world not with the careful eye of the expert, but with the wild, unreasonable gaze of those who have not yet been told what is possible.

For in the end, what is life if not an endless "what if?” What is knowledge if not organized curiosity? What is wisdom if not curiosity that has learned to laugh at itself?

Curiosity killed the cat, they say. But oh, what a resurrection!