The wise man accepts his pain, endures it, but does not add to it. - Emperor Marcus Aurelius

In his book “Thus Spoke Zarathustra,” Nietzsche wrote about the concept of “Amor Fati,” or the love of fate. This concept proposes that we should accept all parts of our existence, including the unpleasant and difficult ones, as an essential component of our personal development. We can learn to embrace life even in its most difficult periods if we accept them.

Nietzsche believed that to live is to suffer, and perhaps this suffering transforms us. It’s an interesting juxtaposition.

The talk of pain and suffering is one that always interests me. And no, I am not actively seeking negative emotions; the topic just fascinates me.

Some might say a full discourse on pain and suffering might come off too pessimistic or worse, nihilistic. As some do with Buddhism.

In truth, they are inevitabilities, and what we do with the experience is what Nietzsche’s and some other philosophers teachings are all about.

SENECA

Seneca said, “I judge you unfortunate because you have never lived through misfortune. You have passed through life without an opponent—no one can ever know what you are capable of, not even you.” Alright, that came out aggressive, but let’s stay on track.

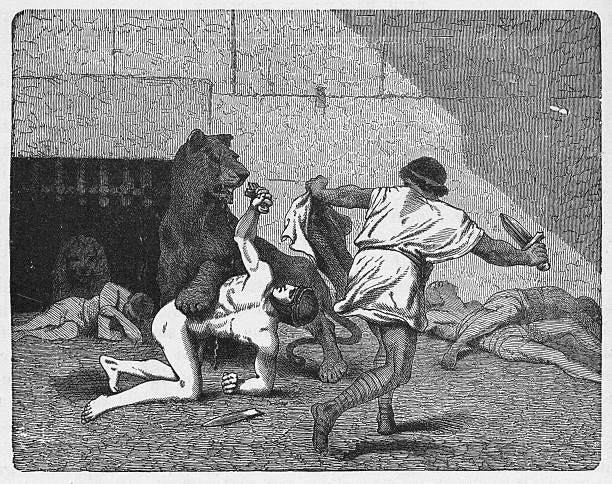

This man believed that to reach the peak of your abilities, you have to experience pain. He lived in the era of gladiators; I can’t blame him. They be like that sometimes. But did it work? Did he make any sense?

The most prominent gladiator in ancient Rome, Spartacus, memorialized in the 1960 Kirk Douglas film of the same name, was likely born in the Balkans, and was sold into slavery to train at a gladiator school in Capua. In 73 B.C.E., still early in his training, Spartacus grew fed up with the abuses of gladiator school. He ran away and took refuge on Mt. Vesuvius. Soon, thousands of other enslaved gladiators fled their schools and joined Spartacus, as he organized one of the most famous uprisings in ancient Rome: the Third Servile War. According to Seneca’s philosophy, if Spartacus had perhaps stayed in the Balkans and worked as a carpenter or something, he’d never be strong enough to lead an uprising.

I know what you are thinking. “He wasn’t the only one who suffered abuse.” True, perhaps he was just more courageous. What birthed this courage, though? Well, the man Seneca said a lot of things: ““No person has the power to have everything they want, but it is in their power not to want what they don’t have and to cheerfully put to good use what they do have.” He was trying to say that Spartacus already had that dawg in him, and all he needed was the right amount of pain. Interesting, isn’t it? He has simply just told me that until I go through some tremendous amount of pain or very likely to die situations, I will not know what I am truly capable of. I am capable of binge watching film series for very long hours and engaging in deep conversations. Thank you, Seneca but I’m fine. I get it. I understand the man, but he’s seemingly too enthusiastic and may be seen as too much. Today’s gladiators are on Twitter and frankly, they don’t need much. A lil bit of unemployment and unlimited data should do the trick.” No uprisings too, just gender wars and who pays on the first date?” We are fine, sincerely.

If there is anything I support about Stoicism, it is definitely its stand on pain. The Stoics take a very different view of misfortune than most people. They expect mishaps and use them as opportunities to hone their virtues. That is not to say that they are glad when troubles beset them, but they try not to lament them needlessly, and they actively seek benefit wherever possible.

Imagine breaking a leg and needing to sit in bed for four months while it heals. A Stoic would attempt to guide their thoughts away from useless “woe is me” rumination and focus instead on how they might do something productive while bedridden (e.g., write their first book). They would try to reframe the event as a way to cultivate their patience and become more creative.

Where there is an adverse event, Stoics try not to let it ruin their tranquility, and instead, they try to derive character-building benefits wherever possible.

Nietzsche

One of Nietzsche’s most significant contributions to our understanding of suffering is his view that it is an essential part of the human condition. According to Nietzsche, life is full of suffering, and it is an experience that everyone goes through at some point in their lives. However, Nietzsche believed that suffering is not something to be avoided or eliminated. Instead, he argued that it can be a source of strength and growth, a means of developing resilience and character.

Nietzsche’s philosophy of suffering is rooted in his belief that the universe is fundamentally indifferent to human existence. He believed that there is no inherent meaning or purpose to life, and that any meaning or purpose we find must be created by us. In this sense, suffering is an integral part of our experience, as it forces us to confront the harsh realities of existence and to create our own meaning in the face of them.

Nietzsche believed that we should not seek to eliminate suffering from our lives, but instead embrace it and use it as a means of personal growth. He also believed that it is through our suffering that we may connect with others and build a sense of community. When we share our pain and our struggles with others, we create a space for empathy and understanding, which can be the foundation for social cohesion and collective action, that it is through these shared experiences of suffering that we can create a sense of shared purpose and meaning.

The perhaps, most challenging aspect of Nietzsche’s philosophy of suffering is his view that suffering is not something to be eliminated or avoided. This can be a difficult idea to accept, especially in a culture that often seeks to eliminate all forms of pain and discomfort. However, Nietzsche believed that by embracing suffering and seeing it as a catalyst for growth, we can become stronger, more resilient, and more alive. This idea is summed up in his famous statement, “What does not kill me makes me stronger.”

Epictetus

No writings by Epictetus are known. Arrian, his pupil states that "whatever I heard him say I used to write down, word for word, as best I could, endeavouring to preserve it as a memorial, for my own future use, of his way of thinking and the frankness of his speech.”

Nevertheless, we cannot sideline his philosophy. Epictetus had a rather interesting point of view. He famously quoted, “That alone is in our power, which is our own work; and in this class are our opinions, impulses, desires, and aversions. On the contrary, what is not in our power, are our bodies, possessions, glory, and power. Any delusion on this point leads to the greatest errors, misfortunes, and troubles, and to the slavery of the soul.”

He simply stated that we have no power over external things, and the good that ought to be the object of our earnest pursuit is to be found only within ourselves. Whatever it is that ‘happens’ to us has nothing to do with you; it is out of your control. It is neither evil nor good. It is simply whatever you make it be. I know you are probably like… “Wait, hold on a sec.” Epictetus maintains that the foundation of all philosophy is self-knowledge; that is, the conviction of our ignorance and gullibility ought to be the first subject of our study. Your interpretation of an experience should be your own and not anyone else’s. You will have to apply some logic, of course. Basically, just tell yourself everything that happens to you is good, and you’ll be fine.

Epictetus is popularly known as a Stoic, but my man had a thing for affirmations. He probably invented sticky notes.

Practice then from the start to say to every harsh impression, "You are an impression, and not at all the thing you appear to be." Then examine it and test it by these rules you have, and firstly, and chiefly, by this: whether the impression has to do with the things that are up to us, or those that are not; and if it has to do with the things that are not up to us, be ready to reply, "It is nothing to me."

According to him, we should not be troubled at any loss, but will say to ourselves on such an occasion: "I have lost nothing that belongs to me; it was not something of mine that was torn from me, but something that was not in my power has left me." Nothing beyond the use of our opinion is properly ours. Every possession rests on opinion. What is to cry and to weep? An opinion. What is misfortune, or a quarrel, or a complaint? All these things are opinions; opinions founded on the delusion that what is not subject to our own choice can be either good or evil, which it cannot. By rejecting these opinions, and seeking good and evil in the power of choice alone, we may confidently achieve peace of mind in every condition of life.

That, my friends, is the gospel of Epictetus.

“There is only one way to happiness and that is to cease worrying about things which are beyond the power of our will.” - Epictetus

Like my very good friend, Oluwafikunayomi will always say, “ROMANTICIZE YOUR LIFE!”

Be mindful and free.

The show must go on.

This is a really brilliant and interesting piece. Now, I want to read more stuff that deals with philosophy.🤭

Lovely article.